organic web

a series - the passage of time

Decay

In high school we visited a landfill for class. I’ll never forget what it felt like to stand there with miles of waste surrounding me, waiting to eventually get compressed into a grassy hill or burned into thin air. Later that same day we visited a recycling plant, as we peered over the ledge at all the heavily compressed plastic bales, the operator told us that only 5% of all plastic ends up getting recycled. All of a sudden, I became viscerally aware of the material weight of my days – in a single morning I’d drink from the plastic straw for my drink which was in a plastic cup which I drank with my plastic box takeout and spoons which was in a plastic bag that overflowed my bins.

Around the same time, my high school became part of the pilot to digitize classrooms, claiming increased environmental friendliness because we were now on the cloud and paper-free. Getting granular, it was likely true, but consequently made it seem as if the lightness of the cloud was all around me.

In reality, there is an immense physicality to the internet. The web is made possible through gigantic underwater sea cables, data is stored in massive centers amongst the midwest, and new technologies require incredible amounts of energy to train. Similar to how I became aware of the pervasive weight of plastic consumption, I became aware of the overwhelming weight of data – an hour of Netflix is 1GB of data, an AI query is 3 times the amount of a Google search, even using upper case letters takes more energy than lower case. When trying to optimize my personal website, I realized the majority of the weight was in images, and I manually resaved each one as .webp in an attempt to decrease the weight. And like plastic, it became incredibly difficult to escape the convenience of technology as protest against the global entropy from consumption.

However, not all fault can be placed on the consumer and there is nuance to the degree in which the utility of technology is worth its weight. The infrastructure of the internet is monetized to remember everything – we pay more as we hold more data and so the data centers are only incentivized to increase in size. Consumption is the basis and underpinning of American capitalism, both in the physical and digital world.

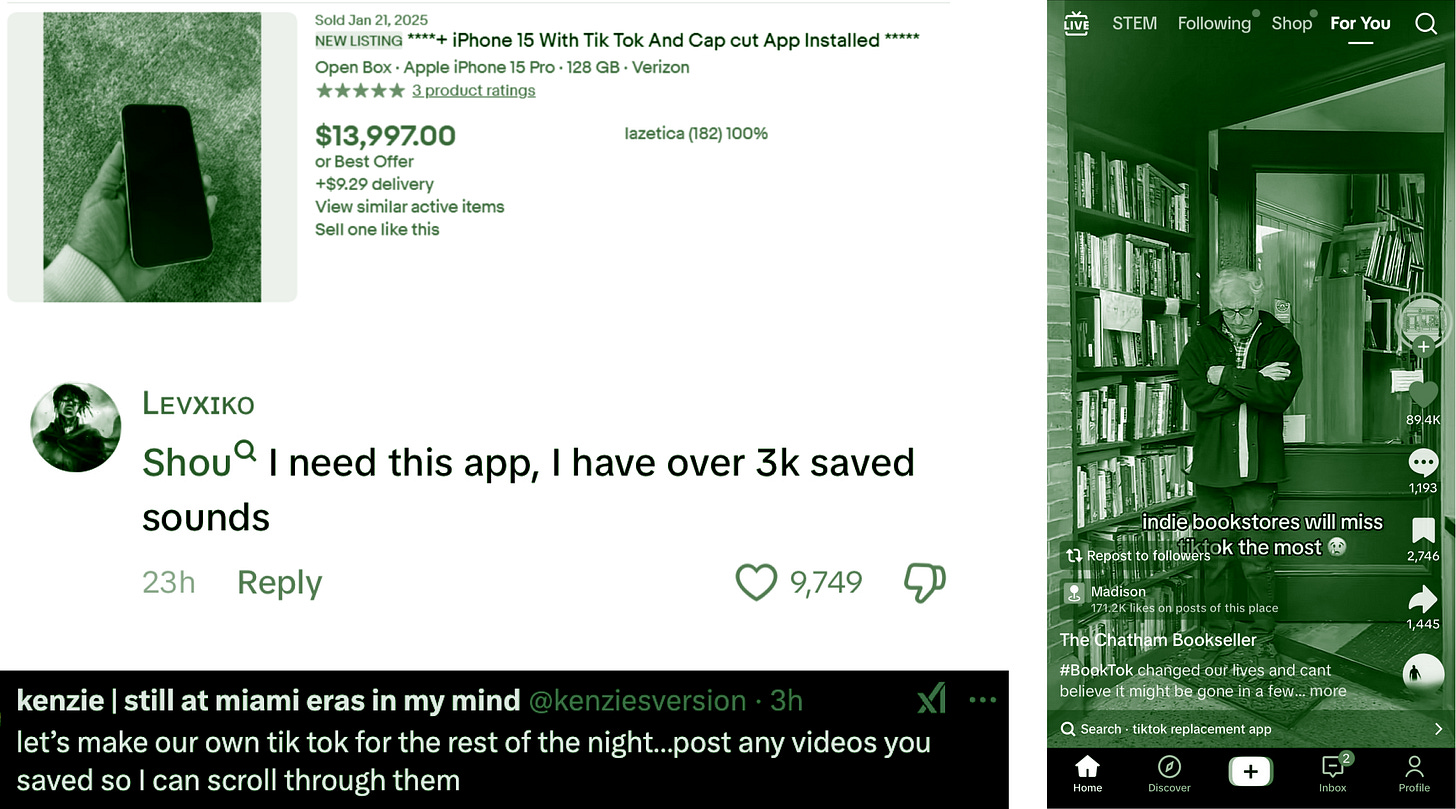

Yet the internet still bears likeness to ecological principles - links rot and decay; by the time I decided to publish this essay some of the links I referenced had already disappeared. However, disappearance is often without warning – entire ecosystems can erase overnight. At the start of the new year, millions of users mourned the imminent loss of TikTok as the app slowly went dark. Even though data could be exported and saved it didn’t mean much as the exported JSON consisted of links to videos still hosted on TikTok itself. That same month, on a smaller scale, I discovered an online design community was fully winding down and all data would disappear from the site in May.

With the reality of impermanence, comes the struggle for preservation. When I went to an event in November at the Internet Archive, they opened with a 5 minute video about their fight to preserve the internet as supported formats disappear and news and media outlets cease operations. Beyond preserving nostalgia and culture, archival was particularly important in recent times as the Trump presidency began to obfuscate important information from HHS and CDC websites relating to LGTBQ and gender identity. Despite the importance of their work, the Internet Archive has suffered in the last year in struggles ranging from DDoS attacks to DOGE funding cuts - the memory of the internet remains fragile and fleeting.

Archival

The default is to save everything, however, we can’t truly save everything ourselves. And with that, what if we embraced the ephemeral and temporal? Isn’t that what the living do? Internet artists have been exploring this idea of temporality on the internet for a while – Laurel Schulwst’s Internet Onion project had the lifespan of five weeks (of an actual onion), Everest Pipkin’s Anonymous Animal was a web essay that only played on the hour, and Elliot Cost’s File Life project had the artist going around collecting people’s files on a USB to symbolically destroy it at the end of the tour; coincidentally enough, the very website dedicated to that project has fully decayed and disappeared as well.

What these projects show is that embracing the temporary is to accept the passage of time, the ebbs and flows of life, and the shifting versions of self. Growing, changing, and decaying is what the living do. Understanding life’s ephemerality increases the importance of archival – instead of remembering everything, we should think deeply about what we want to remember. If the web obscures the true nature of the world, that everything will disappear, then I would have to build it myself.

Cycles

Outside of the historical importance of archival, I sought to understand how it played into the individual’s day to day. I saw principles in the cycles of creation and decay shared across both natural cycles and creative cycles, and saw an opportunity to join the two. As a serial digital hoarder, I save so much – screenshots between photos, thousand item are.na channels, a notes app of one-liners: I’m holding onto so much it falls through my hands. We collect as a form of noticing and remembering – perhaps it colors a perspective or recalls a feeling buried inside us. We collect with the intent of synthesizing and creating – an ever running to-do list. But if we don’t act, creativity will linger at the door and disappear.

I created a transient file storage for creatives (you can try it at linkdump.connie.surf). You can save idle sparks of inspiration throughout the day on a locally stored web canvas (no user accounts necessary). The catch is, these files will disappear within a user-defined set of time, only to be saved as a CSV for local storage so essentially nothing is stored on the cloud. By embodying the transience of inspiration, temporaneous file storage will serve as a catalyst for creating and remembering.

Sometimes I think the internet is purposely built for remembering too much as a revenue driver – we pay more as we hold more data. But we need to let go to allow for transformation of our ideas and ourselves. To allow a proper goodbye to remnants of the past, what better than to create from the experiences which made us who we were in that exact point in time?

Request for feedback 🍃

If you’ve used or want to use link dump, let me know I’d love to chat about your creative process and experience using it for 10-15 minutes! Sign up for a slot at this gcal link or give feedback through this form.

Afterword 🌳

I wrote the initial draft of this in March and held off on publishing because I wanted to create an interactive version for this as well, but I felt like it still wasn’t the right shape - there were a lot of examples per theme I wanted to include that became too much to include into one essay (as evident in the image above) - expect a fuller archival index coming soon this summer!

I find it semi-ironic that I ended up experiencing the same process that I wrote about in this essay but also realize the limitations of a time-bound nature of things - I wanted to get it done earlier but many external factors cropped up preventing me from getting it to what I want - hence this being more of a part one

Which instills the question - I will probably be adding more features to extend the time slightly (?) and have better and more organized CSV export archival

As a designer developing for the first time, this was a culmination of many, many, hours and is still not done! I realized I could do a lot better with onboarding, but I got so tunnel-visioned into making it work it became harder to sketch out ideas. It was also interesting seemingly difficult features took less time than thought, and supposedly simple ones took much, much longer.

Although it’s been a while since I’ve graduated, summer always reminds me of this poem; time is passing!

Thank you Belinda for helping me edit this 🎐

Love this Connie! 🤩

Connie, this is incredible. I love the way you sat on this idea since march, with the intent of making it interactive and giving us as much as possible. as a designer developing for the first time, you fucking killed it.

very interested to see how this evolves and what else you make from it.